The Journey of Afrobeats: Before, Now, and Next

What is Afrobeats? This article gives a historic overview of the journey of Afrobeats, mostly in Nigeria, as a cultural movement, its present state and theorizes on its future potential. It cites interviews from the authors’ weekly Instagram Live series titled “The Journey of AfroBeats” featuring industry stalwarts such as DJ Jimmy Jatt, Sound Sultan and Sir Banko.

The Overview

Before - Before (Afrobeat to Afrobeats - Those who lit the torch)

Now Now (Modern Pioneers - From Kennis Music to Sony Music West Africa)

Where We Dey Go-Go? We Dey Go Up (The revolution, Modern Colonizers, Afrobeats as a way of life and culture)

Before - Before

It’s Friday, April 5, 2019, and we walk into the Apollo Theatre with a few friends. We are all excited at the prospect of spending a Friday night revelling in the energy of an Afrobeats concert instead of the typical Friday night bar run. Burna Boy is slated to perform and he’s sold out this historic Harlem venue. He is not the first African to have achieved this feat, but he is the first of Nigerian descent. NYC’s DJ Buka sets the stage with Afrobeats dominated by Burna Boy’s older songs as the medley crowd of Nigerians, Kenyans, Jamaicans, African-Americans and a host of people from other African and Caribbean countries all bask in the music and await Burna Boy.

When Burna Boy eventually makes his appearance, the crowd’s reaction is electric. His distinct Afro-fusion - a sub-genre of Afrobeats - seems to defy borders, which makes sense, as Music has always been said to be more about the emotions it evokes than the actual words. For us, it is this shared connection to the music in the crowd that has us thinking about the journey of Afrobeats, and how it has evolved to this point.

Technically, Afrobeats is a broad sweeping term for wide swaths of contemporary pop music made in West Africa and its diaspora. Music in this category is syncretized with various genres such as House music, Hip Hop, Soca, R&B and other West African sounds and rhythms.

For us, it transcends this definition. It is a lifestyle, a testament to the Pan-African spirit, our culture and shared rhythms, especially since the sub-genres and sounds grouped as Afrobeats are often distinctly different.

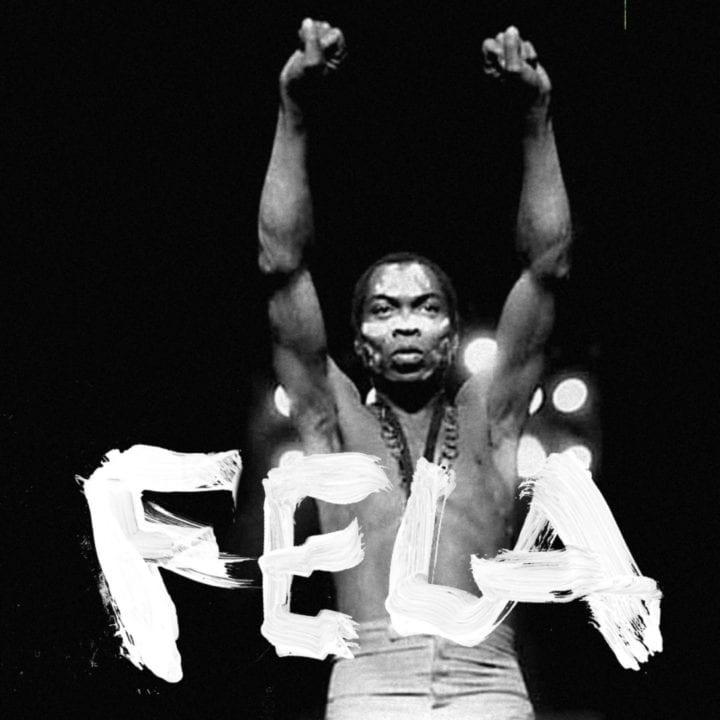

Afrobeat(s) purists have always strived to make people understand that Afrobeats is not to be conflated with Afrobeat. [Afrobeat is a distinct genre pioneered in the 1960s by the legendary Fela and characterized by musical styles such as fuji music and highlife and American funk and jazz influences].

Making and understanding this distinction is very necessary, and people interested in the movement should be precise in how they refer to these two genres. However, in our treatment of Afrobeats history, we seek to blur these lines. While the goals and sound signatures of Afrobeat may be different from Afrobeats, Afrobeat is still a progenitor to Afrobeats. The work of Fela Kuti, E T Mensah, Babatunde Olatunji, Eddy Okonta, Onyeka Onwenu, Sonny Okosun and numerous other pioneers served as a template and inspiration for generations of Afrobeats artistes after them.

Fela, Sonny and others gained international recognition by crooning protest songs about Pan-Africanism, against corrupt governments and about a myriad of social and political issues affecting Africans and their diaspora. Importantly, they made music that evoked emotions in their listeners and spoke to a shared language.

That tradition was carried on by later generations of artistes like Eedris Abdulkareem and Sound Sultan who sang about corrupt government officials and school systems in songs like “Jaga Jaga”, “Mr Lecturer” and “Mathematics”. In an Instagram Live interview with us, Sound Sultan spoke about what it was like being an artist in these times. He recounted wanting to just make music that was amazing to listen to, but also feeling the burden to make music that spoke to the experience of his fellow Nigerians.

And it lives on today, in recent years, Burna Boy has drawn attention to the lasting effects of colonialism in his song “Another Story”, New school Rema asks the Government what do they really governise and warns of a revolution as he subsequently sings in tandem about the girl he wants to wine on, all on an Afro-Trap beat in “Rewind”, perfectly portraying the influence of Afrobeat, even as Afrobeats fuses more and more with contemporary sounds.

Now Now

Many people framing the conversation about Afrobeats in the diaspora today refer to Beyonce’s homage to it in her recent album “The Lion King: The Gift”, and how it is serving as a tipping point/gateway for Afrobeats in the diaspora.

Arguably, in recent times, this has been the best form of validation for the movement, but even before Beyonce paid her dues to the movement, there have always been Afrobeats tracks crossing over. There was D’banj’s “Oliver twist” which broke into the UK R&B charts in 2011 and eventually got D’banj a deal with Kanye West’s GOOD Music. There was also Fuse ODG’s “Antenna” in 2012, Ayo Jay’s “Your Number” in 2013, Davido’s “If” in 2017 and, more recently, Afro B’s “Joanna” which topped charts in the UK and US.

The faces of Afrobeats today are artistes like Davido, Wizkid, Burna Boy and Mr Eazi, but when we think of Afrobeats' current state, it’s really artistes like 2Baba, with his genre-defining African Queen, that serve for us as that bridge between Afrobeat and that cadre of legends to the newer ambassadors of the movement. [Honorable mention to Lagbaja who was active between the late 90s to early 2000s and is purely Afrobeat.]

Labels like Kennis Music, Storm Records, brokered this middle wave and brought artists like 2face, Sound Sultan, Eedris Abdulkareem, Goldie Harvey and Tony Tetuila, artistes whose names are often forgotten in conversations that mostly centre the old guard and the new front runners.

DJs are often forgotten in these conversations, some of the prominent DJs from this era being DJ Jimmy Jatt and DJ Humility. In an IG Live discussion with DJ Jimmy Jatt, he painted for us what it was like to be a part of the movement at that time, assuaging parents’ and other well-wishers’ concerns about their choice to pursue an art that was widely looked down on. One story DJ Jimmy Jatt recounted that stood out to us was a story about the first time he got paid for a gig at a Bank; and how that payment, a small sum now looking back, seemed so big at the time and signalled to him that there was progress being made in being an ambassador for the culture. Thanks to the work of these pioneers, we now have other DJs like DJ Spinall, who was the first African DJ to play at SXSW in 2015, DJ Xclusive and DJ Cuppy exploring and proliferating the newest Afrobeats inspired sounds.

These labels and pioneers have traceable lineages that lead directly to acts like Wizkid [Eldee, Banky W], Burna Boy [960, Aristokrat] or influenced acts like Davido [Mo'Hits] that are prominent today.

Meanwhile, one of these frontrunners, Mr Eazi, was earning his stripes in Ghana, being influenced by the Highlife sounds of Ghana. There has always been a synergistic relationship between Ghanian and Nigerian music, with a lot of Nigerian highlife being influenced by sounds from its fellow anglophone neighbour. Mr Eazi continues this tradition in creating Banku Music, which he describes as fusion music, a mixture of genres and influences. He says he birthed it by experimenting with and mixing Ghanaian highlife with Nigerian chord progressions and Nigerian patterns. Essentially, it is a mixture of Nigeria and Ghana and it is his own niche/subgenre in the wider Afrobeats culture.

Apart from these frontrunners, there are numerous other players. There is Naira Marley, whose move to Peckham at 11 has influenced his style, creating what has been termed Afrobashment, an interesting concoction of his own Nigerian roots, grime, and dancehall. His breakout song Issa Goal was Nigeria’s 2018 World Cup Anthem, and let people know he is one to listen to.

Really though, it has been his follow-up hits that have seen him unite swathes of fans with backgrounds ranging from street conductors, known as Agberos, to the “Ajebutter” kids in Lekki neighbourhoods into his devoted army of fans known as Marlians. A close associate of Naira Marley is Zlatan, who has been on the Nigerian music scene for a while. He got his first big break in 2014 when he won the Airtel-sponsored One Mic talent show in Abeokuta, Ogun State. He seems to have slowly mastered music that’s authentic to “the Streets” and makes its way into mainstream culture. He demonstrated this mastery on Chinko Ekun's hit song ”Able God” and took this further with “Zanku” [Zlatan Abeg No Kill Us] which denotes his ability to make listeners excited and doubles as a hit dance.

Zanku has followed a long tradition of afrobeats inspired dances such as Azonto, Skelewu and Shaku Shaku which are recognizable and see African kids in the diaspora serving as tutors to their international friends who want to be hip with these moves. Then there’s Teni, who transitioned from an Instagram freestyle star to writing for Davido and then eventually making her own hits that just resonate on a very personal, nostalgic level. Another article could be dedicated to just exploring these artistes and their contemporaries and it still wouldn’t be satisfactory, but as a whole, they represent all the work done so far and show the promise this movement holds to transcend borders and become a global influence on the scale of Reggae and Soca.

Consequently, to us, Beyonce’s the Gift, is not the crescendo or final stamp but just another milestone of Afrobeats march to global incorporation.

Already, we see modern colonizers beginning to claim their stake, and while we welcome the outside investments, we think it is necessary that Africans still control and take charge of the narrative. In an Instagram Live conversation with Sir Banko, Former Davido Music Worldwide (DMW) president and current Head of Sony Music West Africa, he tells us of his plans to ensure every talented artiste can get their voices heard. We believe this is very possible with today’s streaming solutions. However, we are glad to hear his view that a focus for him is in making sure that Africans don’t just have a minority seat on this table, but actually have major stakes and direct the flow so that we are not left with a second scramble for Africa where we are left on the losing end again.

Where We Dey Go? We Dey Go Up

Afrobeats today is wide-sweeping, and we think it subsumes Afrobeat in the way the Atlantic subsumes Niger. Afrobeat was an important tributary, but Afrobeats has taken those influences and carried it around the world in a way that we feel now supersedes “World Album” nominations. Especially when an Afrobeats’ inspired Album [“The Lion King: The Gift”] earned nominations in pop categories in the same year, Burna Boy’s African Giant was nominated in the “World Album” category. We believe Afrobeats has superseded that “World” box, which in the context of the Grammy means anything foreign or other to the Recording Academy, and ironically when used as in “World Tour” means everywhere else except places in Africa which are again seen as “Other.”

We have a new wave of artistes including Cruel Santino (formerly known as Santi) who recently got signed to Atlanta’s LVRN and makes music so eclectic, it’s defied any genre -definition and has led to him being recognized as the face of the Alté Movement. The Alté movement is a cultural revolution and houses various artistes whose works are all as different from each other as they are from the mainstream, hence leading to the moniker Alté. However, before he reinvented himself as Santi he was known as Ozzy B, and really engaged with new media such as Twitter and Soundcloud, and used these to bypass the gate-keepers of mainstream Afrobeats.

Rema, mentioned earlier, has a sound so distinct, with hints of Trap, Indian and Arabic rhythms, that many people in Nigeria dismiss his work as not truly being Afro influenced. It’s interesting because Rema himself often has to point out his work is still influenced by the Afro sounds and just because he has redefined it and made it his own, doesn’t dismiss it from the larger culture.

Fireboy, whose breakout single “Jealous” featured African harmonies with Soul and Country elements also brings a fresh perspective to the industry with his music which he terms “Afro-Life”, a style that’s as concerned with relatability and uses its catchy beats in a purely support role. His sound is in contrast to Remy Baggins whose beats have wide-ranging influences but are always dominated by his liberal use of 808s. In a conversation with him, he says he began using 808s because of technical issues, and they eventually came to dominate his sound since they were the only bass sounds he could stand. Now he doesn’t have those same challenges but continues to use them both to pay homage to the 1980s and as an expression of his production genius.

Lady Donli who is always classified as belonging in the Alté scene, self describes her music as; a mix of R&B, Hip-Hop, and alternative Jazz crushed to bits with airy, raspy vocals, in an earthy wooden bowl. What really stands out about her music to us, is its determination to convey happiness, and bring joy to listeners, even as it highlights struggles recognized by the listener. Her tendency to emphasize her Northern roots and make music that uses sound patterns from that culture is also beautiful to listen to. Her visuals also pay homage to Pan-Africanism with her photos referencing pioneers in the African music scene and her videos inciting nostalgia in viewers who recognize it as a love letter to the Nollywood flicks we grew up on.

Jess ETA, still really underground, makes music with influences ranging from R&B to EDM to Trap and Hip-hop. He describes his sound as an Afro influenced fruit mix, and his experiments are anchored by his brilliant production and songwriting prowess. This new guard is ensuring we’ll have an unbroken chain in our evolution into global cultural assimilation. We know that, in a few years, we’ll be at a Cruel Santino concert with a diverse crowd that transcends the African Diaspora, and yet speaks to and is understood, really understood by the wide-ranging group of people at the scene.

Hip-hop as a culture helped African Americans reinvent and take back power over how they were perceived. Helping to blunt their traumas and pain, we see Afrobeats as similar, but for all black people and their diaspora, serving as a beacon, showing the world just how much we can be seen.

However, when you consider Hip-hop, even though it helped African-Americans in processing their trauma and telling their stories, the statistics of who is profiting in the background tells a sad tale. Even as hip-hop has become a staple of musical appetites around the world, the makers of Hip-hop music, mostly African-American, are not representative of the executives running the show.

There was a point where the leadership in the Hiphop/R&B industries was more representative; that has however been reversed and even in Hiphop, a culture created by African Americans, we see less people in leadership than there are African Americans in the general population.

We want to make sure this doesn’t happen to Afrobeats; we want these stories to be told by us and owned by us, and the majority of seats to belong to us, so that even as outside investment money pours in, it should be partnered not chaired.

And we should also be vigilant, so that we don’t have representation in the beginning and then slowly get exploited again with our talents and product being treated as a raw commodity without our communities being given back to.

Efforts like Mr Eazi’s Empawa are a beacon in a fog, helping to elevate and showcase African talent, and are particularly exciting since they are by us, and for us, and help to highlight and develop local talents.

We want us all to do more for the movement. We have come a long way, but still there is work to be done, and we should not shirk from doing this work! It could be as little as resharing the work of your unknown producer friend with the breathtaking melodies. Who knows? You could just be sharing the next frontrunner of the movement!

Writers:

Solomon Oluwajoba Kehinde aka JayKayKenny [Shortman] is a Toronto based comedian, content creator, actor, entrepreneur and graduate of the Toronto Film School.

Nanmwa Jeremiah Dala is a writer, engineer, and talent manager based in New York.

References

The evolution of Afropop: A history of the music scene

Afrobeat(s): The Difference a Letter Makes

How Beyoncé Made 'The Lion King: The Gift'

EMPIRE Signs London AfroWave Singer Afro B: Exclusive

Introducing Mr Eazi, the OVO and Wizkid Favorite Bringing Afrobeats to the Masses

The New Guard of Nigerian Musicians

Why Hasn't the Hip-Hop Boom Pushed More Black Executives to the Top?

What The Rise And Fall Of Black Leadership In The Music Industry Says About Equality Today